Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology Biomolecular Engineering & Marine Biotechnology Lab.

Beetles represent an extremely diverse group of organisms with over 350,000 species existing on Earth. Observing the natural world, we can encounter beetles possessing exoskeletons with a remarkable variety of shapes and colors. Beetle exoskeletons have attracted significant attention in the field of industrial material development due to their lightweight nature combined with diverse mechanical properties. Recent research has revealed that these superior properties are derived from micro- and nanostructures that are precisely controlled by biological systems. Our laboratory actively pursues research aimed at the goal of applying beetle exoskeletons to materials, focusing on elucidating the formation mechanisms of microstructures that produce these outstanding properties and their application to novel material development.

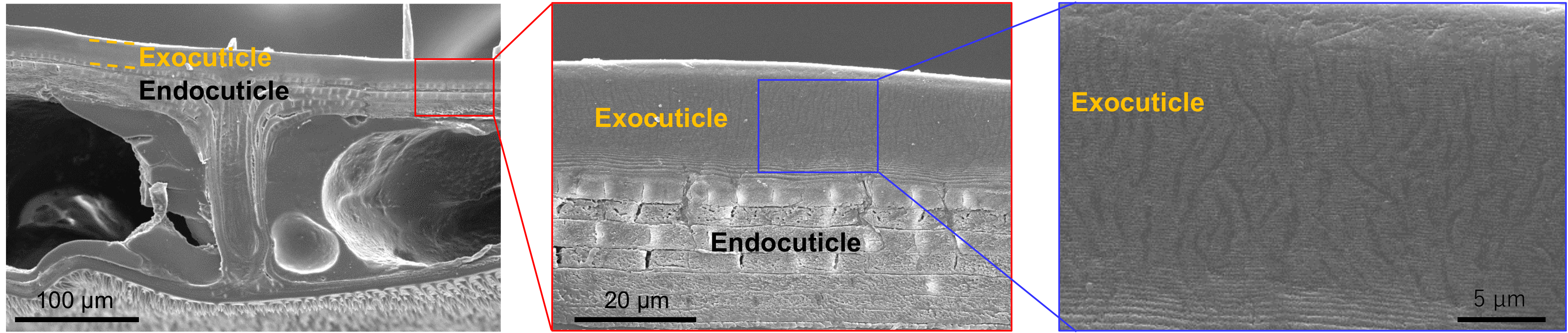

Structure of Beetle Exoskeleton

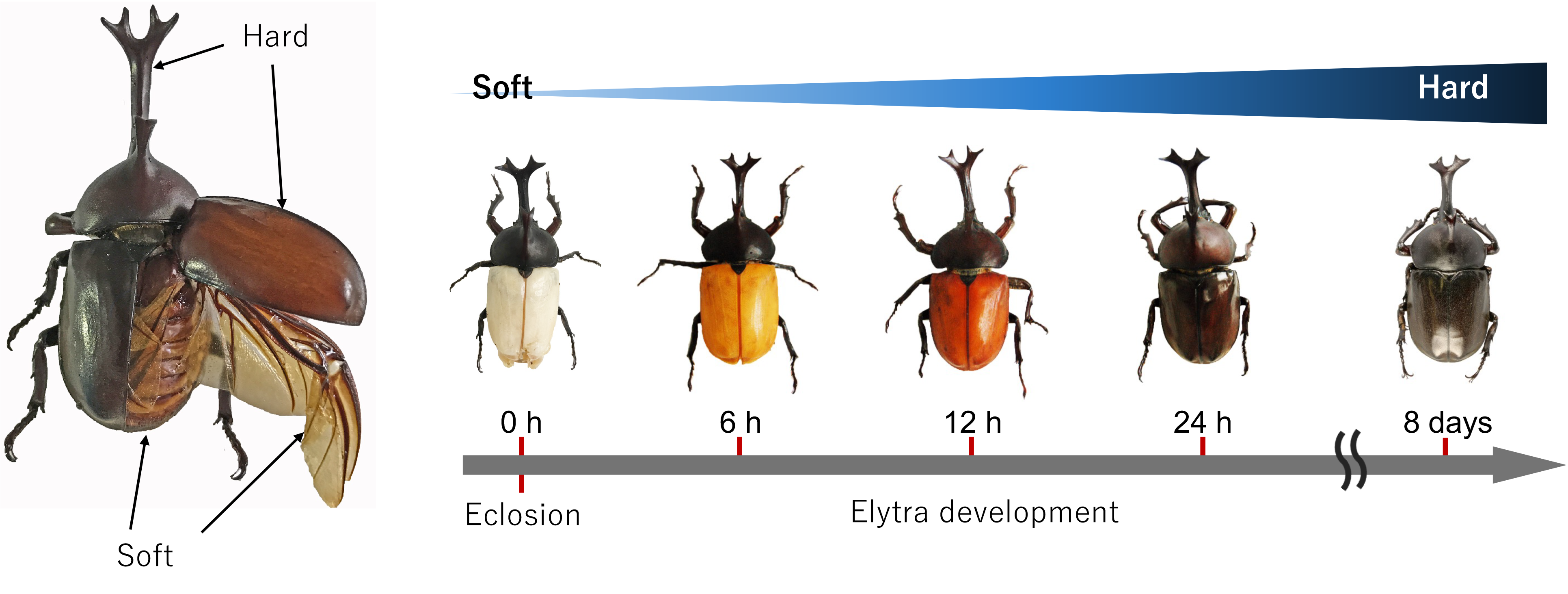

The horns of male rhinoceros beetles are extremely hard as they function as weapons in territorial disputes, while the leg joints composed of the same components exhibit flexible properties (Fig. 1). Additionally, the back side of the body of newly emerged adults undergo rapid hardening within a short period after eclosion, resulting in dramatic improvements in mechanical strength. Although these exoskeletal parts exhibit seemingly completely different properties, their main components are composed of chitin and proteins. It is believed that the molecular-level complexation of chitin and proteins enables the formation of body parts with diverse structural and mechanical properties. Our previous research has elucidated the differences in microstructures among beetle exoskeletal parts with different mechanical properties.

Formation Process of Beetle Exoskeleton

The hard wings covering the dorsal part of rhinoceros beetles are called elytra (Fig. 2). The elytra of newly emerged rhinoceros beetles are white and flexible immediately after eclosion but undergo rapid blackening and hardening within several days.

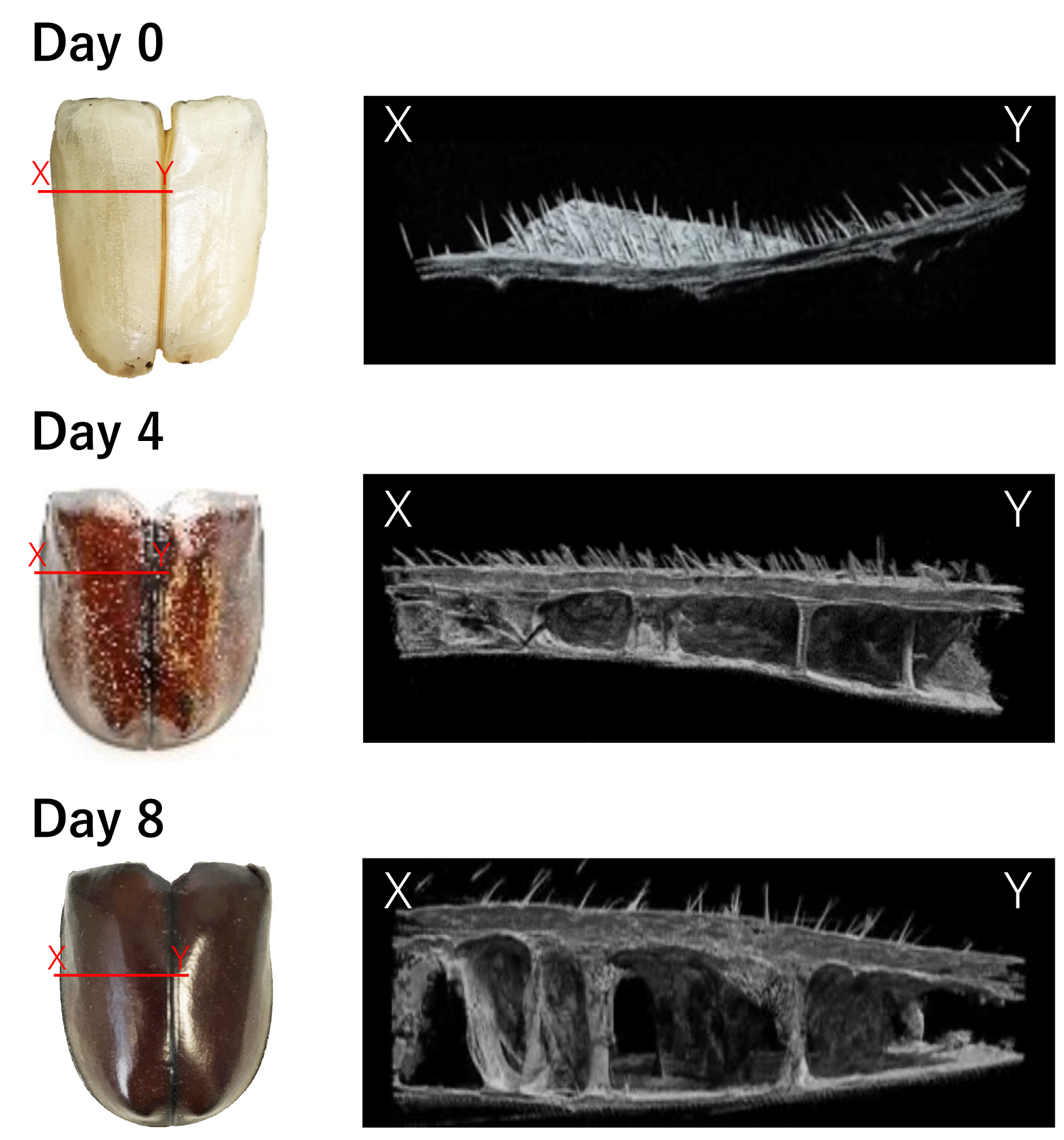

We conducted detailed analysis using high-resolution CT scanning of elytra from immediately after eclosion to predetermined time points post-eclosion (Fig. 3). While the elytra immediately after eclosion exhibited a single-layer sheet-like structure, we observed structural changes over time including separation into a two-layer structure, formation of pillar-like structures, and thickness increase of each layer. These results revealed that dramatic structural changes occur within a short time during the maturation process of elytra.

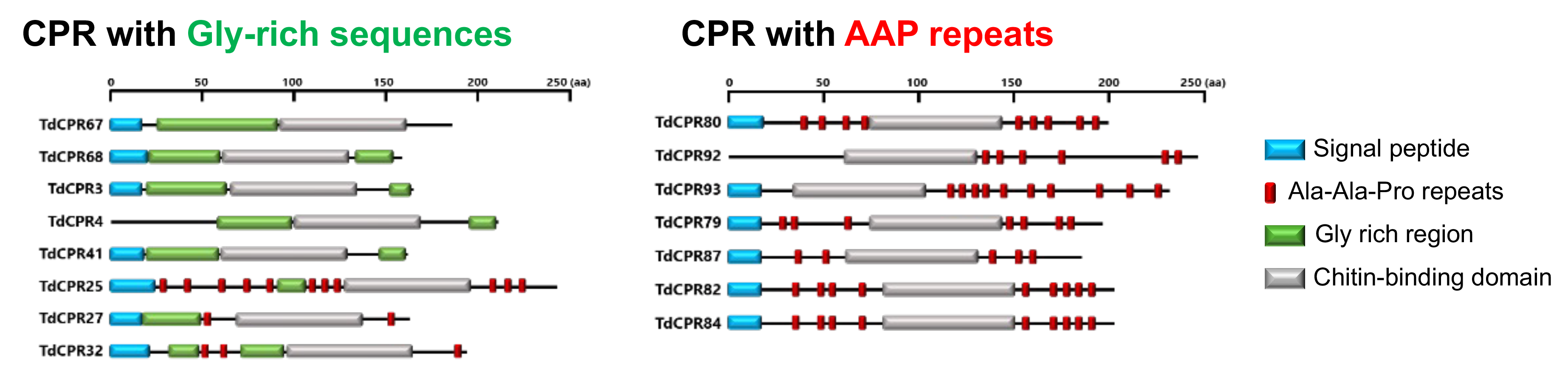

Cuticular Proteins Involved in Exoskeleton Formation

The proteins constituting beetle exoskeletons are called cuticular proteins and are known to play important roles in exoskeleton formation. By multi-omics analysis of rhinoceros beetle and its elytra, we identified cuticular protein groups expressed at each stage of cuticle formation (Fig. 2-4). Furthermore, we discovered characteristic structures previously unreported in the amino acid sequences of cuticular proteins expressed at each formation stage. Future detailed functional analysis of these protein groups is expected to establish chitin material structural control technologies. These research findings hold the potential to contribute to the creation of high-value-added materials with low environmental impact through effective utilization of chitin, and are expected to contribute to sustainable material development.